THE BLOG

It’s Time to Get Serious

RIRA and Value Creation Rebundling for CRE

In late 2025 AI crossed a tipping point. What was, since the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 an exciting, but somewhat maddening, new technology, morphed into being something much more robust. Yes, the ‘Jagged Edge’ of capabilities still exists, but an increasingly large number of business tasks and workflows are now firmly within AI’s purview. Put simply, we have reached the moment we need to take all of this seriously.

The Steam Engine Analogy

In the 1880s steam engines in factories started, slowly, to be replaced by new-fangled electric motors. And great productivity boosts were promised. But they never occurred. It turns out that replacing the power driving a central shaft with chains and pulleys made next to no difference to how well factory workers could actually work. It wasn’t until nearly four decades later, when factories themselves were redesigned, work disaggregated, and instead of one central power drive, a multitude of motors, serving a multitude of different processes, were introduced, that we see any meaningful productivity boost. And then it went ballistic - productivity soared and the roaring 20’s were underway.

Leveraging the new technology was impossible when bolted on to current workflows. Only when workflows were redesigned to specifically match the capabilities of the new technology did change occur. One needed to bake a new cake, not just put cream on top of the old one.

And now, history is repeating.

The ‘J’ Curve

Stanford Professor Eric Brynjolfsson has written about what he describes as the J-Curve. Where when new technologies are introduced, productivity actually declines for some time, before turning upwards dramatically. And this occurs because we have to invest in the intangible capital of new processes, organisational design, workforce training and complementary innovations, in advance of reaping any rewards. It is not until all of this melds into place, flywheels emerge, and benefits compound, that we stop being in the red.

And this is where we are now.

Changing Gears

The last two months of 2025 saw the release of ChatGPT 5.2, Gemini 3 and Claude Opus 4.5. Three enormously powerful frontier models. On top of which have emerged UX developments making interacting with the underlying power of these models increasingly easy. Google released Antigravity, OpenAI Codex 5.2, and Anthropic linked Claude Code with Opus 4.5. All of these are tools for developing ‘agentic’ systems (where multiple task-based ‘agents’ are strung together), primarily aimed at developers. What is emerging that is a step change is that these types of tools are being given interfaces that are, for the first time, accessible to non-coders. Most notably the new ‘chatbox’ version of Claude Code available via their desktop app.

We are very rapidly moving into the era of the ‘Business coder’. Where someone with no, or very limited coding skills, can summon up working software simply through natural language. The ability to explain one’s requirements clearly is now the defining skill. How well you understand ‘WHAT’ should be built, and how it should work, is the new superpower.

The barrier between thought and actualité is fading away.

We are all coders now.

I exaggerate to make the point, but give it another year and this absolutely will be reality.

But… how to know ‘WHAT’ to build?

Introducing The RIRA Framework

Let’s assume your ambitions stretch beyond having AI draft your emails, or summarise your documents. Let’s assume you’re ready to be serious.

Then you need to take The RIRA Framework (plus its two complements - the CRE Automation Matrix and the CRE Prompting Frameworks) seriously, because it is specifically designed for those thinking hard about how the real estate industry is set to change and how they, and their teams and companies, need to reposition themselves to maximise AI leverage.

What is it?

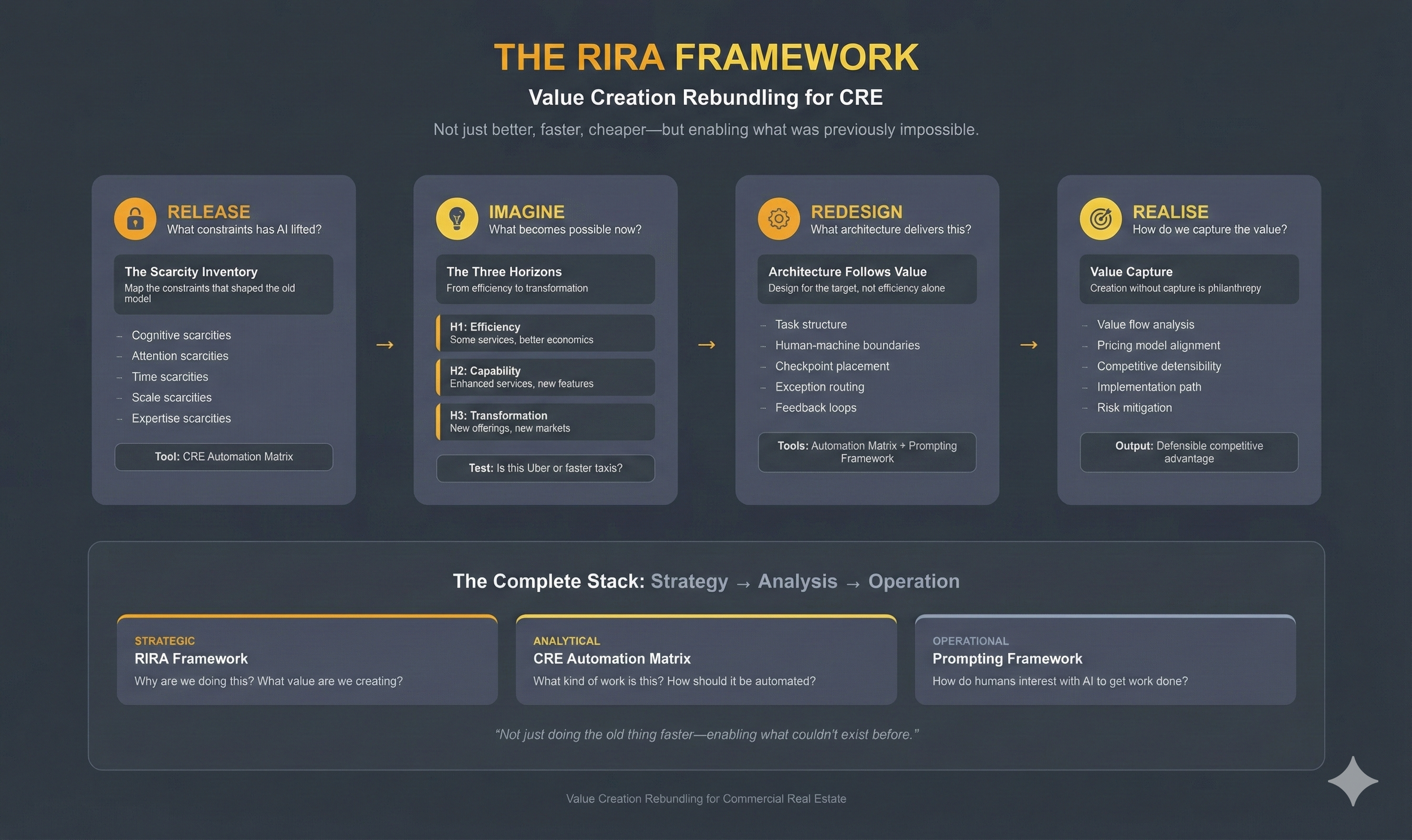

‘RIRA (Release–Imagine–Redesign–Actualise) is a strategy-to-execution framework for rebundling value creation in commercial real estate under conditions where AI materially changes the unit economics of analysis and content production.

It helps teams move beyond “using AI” towards engineering repeatable, evidence-based workflows that:

(i) explicitly surface what constraints are removed, and introduced, by AI

(ii) identify the new possibilities that become economically viable

(iii) redesign work into verifiable modules with controls

(iv) capture value through implementation, measurement, monetisation, and defensibility’

The critical terms are ‘constraints’ ‘new possibilities’ and ‘verifiable’.

AI both removes and introduces constraints: time and cognition are no longer scarce, but trust, confidentiality, and governance become critical.

AI enables us to be more efficient, or add new features, but far more importantly, it enables us to do things that were simply not possible before.

And AI makes whether something is verifiable or not, the cornerstone of how we design systems. You cannot, or at least should not, automate anything you cannot verify.

Why It Matters: The Strategic Problem

Al makes it cheap to generate outputs that look professional - memos, drafts, comps tables, market narratives, even pseudo-model commentary.

In CRE, where much value is mediated through decision confidence, risk allocation, and narrative control, this creates a structural trap:

The supply of plausible analysis rises sharply, but…

The supply of trustworthy analysis does not

RIRA is built to solve that mismatch: it forces a shift from “drafting at scale” to verifiable decision support, and from “internal efficiency” to capturable economic value.

What Goes Wrong Without It?

Without a RIRA-like discipline, organisations typically land in one of four bad equilibria:

- Productivity theatre: teams generate more documents faster, but decisions are no better; quality becomes subjective; risk quietly increases.

- Shadow Al: adoption happens informally; sensitive data leaks into tools; auditability is lost; governance reacts too late.

- Brittle automation: organisations automate workflows that should be redesigned, then get exception-handling chaos and reputational damage.

- Uncaptured value: real productivity gains occur, but are not measured, productised, or defended - so the benefit is competed away or simply absorbed as “busyness”

RIRA matters because it treats Al adoption as an operating model change with explicit trade-offs: you release constraints, but you also introduce new ones; you imagine new value, but you must redesign for evidence; you implement, but you must capture and defend value.

Before And After

Before AI, narrative drafting and expert packaging were scarce - and this scarcity was what commanded a premium.

But AI upends this: drafting and packaging becomes easy, a commodity. Everyone can do that.

What everyone cannot do, and probably won’t because it is hard and involves real effort and commitment, is:

Proving it’s right (evidence)

Ensuring it doesn’t break (controls)

Embedding it in real systems (integration)

Getting it to the right people (distribution)

Making stakeholders trust it (governance credibility)

This is what I mean by value creation rebundling: the components that once commanded a premium unbundle, commoditise, and the premium rebundles elsewhere.

Release, Imagine, Redesign, Actualise

The RIRA Framework is not meant as a sequential process. It’s an iterative loop. As you work your way through looking at constraints, and failure modes (which tell you how to verify or where to retain a human in the loop) you’ll develop a feel for how transformative you can be with any given workflow. Some will remain much as is, with maybe some efficiency tweaks. Some will lend themselves to being made more capable. Some though, you will discover, fit perfectly into that ‘value creation’ bullseye.

Within this iterative loop you will use the ‘CRE Automation Matrix’ Framework to understand exactly which tasks to automate, and where value lies, and this will be the subject of next week’s newsletter.

For now, the imperative to grasp is that AI has reached a threshold where dabbling is no longer enough. In CRE, as in all businesses, we have reached the point where considerable change is a certainty, and iterating on the past won’t suffice.

There’s a phrase that does the rounds - “AI won’t take your job, someone using AI will” - but it misses the deeper point.

As Sangeet Choudary put it recently: “New tech collapses old constraints. Once a constraint disappears, the logic of competitive advantage and business model design must be reimagined from first principles.”

In CRE, the constraints that defined value creation for decades - the scarcity of time, cognitive bandwidth, and expert packaging - are dissolving. What emerges in their place is a different scarcity: evidence, verification, integration, governance credibility. The premium rebundles around whoever solves for those.

Bolting AI onto existing workflows won’t get you there. Redesigning around the new constraint set will.

That’s what RIRA is for. Next week: the CRE Automation Matrix, which shows you exactly where to look.

Where the Firm Learns Now:

GCCs and the New Operating Model of Knowledge Work

Last week I suggested that 2026 feels odd because our familiar ways of thinking are not aligning with the world as it is today. We keep trying to explain the world with single-cause stories, hybrid work, AI, rates, geopolitics, talent shortages, and each one is true enough on its own. But experienced together, they create a kind of conceptual vertigo.

This week I want to make one of the quieter structural shifts much clearer: the rise of the Global Capability Centre (GCC) as a default design pattern for large organisations.

Not as a footnote to globalisation, but as a clue to where firms are choosing to build themselves.

The GCC as operating-model infrastructure

A GCC in India still gets described, casually, as “offshoring”. That language is a hangover. It carries the intuition of factories and back offices, things moved for cost reasons, tasks reallocated, efficiency extracted.

What is happening now is more interesting and, I think, more consequential.

A modern GCC is increasingly where large organisations build and maintain the machinery of contemporary knowledge work. Not simply running processes, but owning platforms and capabilities that everything else depends on: engineering, data, analytics, cybersecurity, product modules, AI operations, internal tooling. In many firms, these centres are where competence compounds, where people stay longer, systems get understood deeply, and teams develop muscle memory.

The most important effect isn’t always visible as layoffs “at home”. The more common mechanism is that the next wave of roles, especially the ones that form career ladders and leadership pipelines, land somewhere else. It is growth displaced rather than jobs replaced.

That is a very different kind of shift to the one most public debate is set up to recognise.

What actually gets done inside a GCC (in 2026 terms)

It helps to break GCC work into layers, because they are often conflated:

1) Industrialised execution

These are repeatable, verifiable outputs:

Data engineering and pipeline maintenance

QA and testing

Production analytics and dashboards

Reporting, reconciliations, controls

Operational risk processes, monitoring

This is the “cognitive factory” layer: high throughput, high standardisation, measurable outputs.

2) Platforms and orchestration

The systems and workflows that make the firm run:

Internal tools and automation

Enterprise workflow design

MLOps / AI ops (model deployment, monitoring, governance mechanics)

Cloud and platform engineering

Integration work across teams and systems

This layer is where capability becomes an asset, because once you own the platform, you shape what is possible.

3) Resilience, controls, and risk infrastructure

The nervous system of the organisation:

Cybersecurity architecture and operations

Incident response

Identity, access, and controls engineering

Compliance tooling and audit readiness

Operational resilience programmes

These functions rarely get the glamour, but they have become existential. That pushes them toward scale and continuity.

4) Product and engineering ownership (increasingly common)

This is the significant shift:

End-to-end ownership of services or product modules

Feature development tied to global roadmaps

Data products, model products, and internal “platform as a product” teams

At this point the GCC stops being a support function and becomes part of the organisation’s core building capacity.

The important point is not that every GCC does all of this, but that the direction of travel is clear: these centres are moving up the stack.

Why firms do this: the overlooked economics of coordination

Most people assume the dominant driver is cost. Cost matters, of course. But if cost was the whole story, we would see these centres treated as interchangeable labour pools, constantly shopped around.

Instead we see firms committing long-term capital, large footprints, and leadership attention. That tells you something else is doing the heavy lifting.

The under-discussed driver is coordination economics.

Modern knowledge work, especially in large firms, is not primarily constrained by the ability to hire brilliant individuals. It is constrained by the ability to field coherent, stable, persistent teams that can build complex systems over time.

What kills productivity is not the salary line. It is:

High churn and short tenure

Constant re-forming of teams

Loss of institutional memory

Weak shared context

Senior time spent endlessly recruiting and re-aligning rather than building

A large, well-run GCC can reduce that coordination drag because it often offers:

Greater team stability

Longer tenures

Deepening shared context

Stronger internal labour markets and career ladders

A culture built around platform stewardship rather than constant reinvention

This is a new organisational physics.

Last week I discussed JPMorgan’s commitment to a Brookfield-developed campus in India, institutional-grade capital, not a temporary lease. Microsoft’s India Development Center is one of its largest R&D centres outside Redmond and contributes materially to core Microsoft products and platforms. Over 130 UK firms operate Indian GCCs employing 200,000 professionals. The shift is real.

And once you see it, the GCC becomes less a “location choice” and more a structural choice about how the firm wants to learn and compound capability.

Note: This is not across the board, and the market is changing rapidly. Tier-1 Indian cities face attrition rates of 20–25% in IT roles; Tier-2 cities like Indore, Coimbatore, and Kochi offer 8–12%. That stability matters increasingly for agentic workflows, where deep institutional knowledge is required to train and govern AI systems effectively.

Separately, infrastructure is creating new centres of gravity. Google’s $15 billion investment in Vizag - gigawatt-scale data centre operations and a new subsea cable gateway - signals that AI-era location decisions are driven as much by power and connectivity as by talent.

A historical rhyme: the invisible move

This has echoes of manufacturing, but the similarity is easily overstated.

Manufacturing relocation was legible:

Factories shut

Jobs disappeared from specific places

Whole local ecosystems unraveled

Knowledge work relocation is quieter. It arrives as “global delivery models”, “platform teams”, “centres of excellence”. It often looks, in the moment, like perfectly reasonable corporate housekeeping.

Which is precisely why it has such power.

The story of the last few decades is full of shifts that were operationally rational and politically unreadable until they were entrenched. Supply chains reorganised; politics arrived later, and often with language that didn’t match the structure of the change.

Something similar is happening now.

Public discourse is still most fluent when the issue is visible and physical: factories, borders, trade in tangible goods. Knowledge work is harder to narrate because it doesn’t vanish in a single closure. It thins. It relocates as future growth. It becomes a missing ladder rather than a headline.

In a way, politics helps to hide the shift, not always deliberately, but structurally, because it tends to focus on what can be pointed at, photographed, and blamed. The more important change is often administrative and slow.

Why this connects to London (and other global cities)

A question that naturally follows is: if GCCs are where so much capability is being built, why do firms still invest so heavily in major hubs?

I think we are watching the “office” split into two functional roles, and the split is becoming sharper:

Capability hubs (often GCCs): places where execution at scale, platform building, and operational intelligence are concentrated

Commitment hubs (major global cities): places where client relationships, regulatory accountability, senior arbitration, and legitimacy are concentrated

These are different forms of work. They require different densities, different rhythms, different building types, and different economic logic.

It also helps explain why you can see large commitments to prime space in London alongside large commitments to capability centres elsewhere. The firm is not choosing one geography. It is designing a system with multiple centres of gravity.

The most important mechanism for the West: “missing growth”

If you want one phrase to hold onto, it’s this: missing growth.

The typical effect is not that Western offices empty overnight. It is that:

headcount growth slows

junior and mid-level ladders thin

whole cohorts of roles that used to be created domestically are created elsewhere

platform ownership and learning accumulate away from traditional hubs

This matters deeply for cities because cities do not just depend on jobs; they depend on:

ladders

clustering

progression

the density of early-career opportunity

the social infrastructure of an upper-middle class that compounds skills and civic capacity over time

When you displace growth, you eventually displace the social fabric built on that growth.

That is why this is a city story, not just a corporate efficiency one.

The AI twist

One more nuance is important, even in a GCC operating-model piece.

GCCs are often built to standardise and systematise work. That is what makes them scalable. It also makes parts of them legible to automation. AI does not arrive later as an external disruption; it arrives inside these centres as a force that compresses the very work they were designed to industrialise.

That does not mean GCCs are a short-term fad. It suggests a more complex trajectory:

growth and consolidation now

compression of industrialised execution later

a shift towards orchestration, governance, exception handling, and platform stewardship

This is worth holding in mind because it affects both labour-market expectations and real estate planning in GCC locations too.

But the immediate point remains: today, GCCs are where firms are choosing to build capability at scale.

What this means for commercial real estate

Put all of this together, and you get an explanation for a pattern many of us feel in the market:

Office demand isn’t behaving the way the old models said it should.

Hybrid work is part of the story. Rates are part of the story. But underneath them is a deeper decoupling: organisations are learning to scale capability without scaling domestic space in the way we once assumed.

For CRE, that implies:

A lower long-run demand ceiling in many Western markets, even if prime assets remain resilient

More polarisation between buildings that support high-stakes coordination and those designed for routine execution

Weaker development optionality (less need for large “growth leases” and expansion rights)

A sharper distinction between cities that host commitment and cities that host capability

And perhaps most importantly:

the office becomes less a universal container for work and more a specialised instrument for particular human functions.

That is an argument for clarity, not simply optimism or pessimism. We have to deal with the world as it is.

A closing question

If GCCs are becoming operating-model infrastructure, places where competence, continuity, and platform ownership increasingly compound, then we have to ask a question that commercial real estate has not been forced to ask in decades:

Where does the organisation actually learn now?

Because where it learns is where it eventually invests, not just in buildings, but in people, influence, and long-term relevance.

Next week I’ll add the accelerant: AI. Not as a general technology story, but as the force that re-sorts work into execution and judgement, and, in doing so, reshapes both offices and participation in value creation.

For now, one question to leave you with:

If growth is being displaced rather than destroyed, what would it mean to value office markets by “missing absorption” as much as by vacancy?

Why 2026 Feels Odd

I keep noticing something.

We are having many parallel conversations about the future - AI, offices, global talent, cities, productivity - and each one is coherent on its own terms. Yet when you hold them side by side, they create a strange cognitive dissonance. The world feels both more connected and more fragmented; more productive and less stable; more technologically capable and less socially confident.

When the present feels like this, I’ve learned to look for structural changes that sit underneath the headlines. Often, they aren’t dramatic. They’re quietly administrative. They arrive as “operating model”, “capability”, “platform”, “centre of excellence”. And then, ten years later, we wonder how the ground moved beneath us without anyone quite noticing.

One of those signals is the Global Capability Centre. The GCC.

The GCC as a Clue

“A GCC in India” can sound like an old story: globalisation, cost arbitrage, offshoring. Factory logic applied to desks.

But the centres being built now, especially at the scale that global banks and technology-heavy firms are committing to, are something else in practice. They are places where organisations build and maintain the machinery of modern knowledge work: engineering, data platforms, cybersecurity, analytics, internal tooling, increasingly AI operations. In some firms, the GCC is where the organisation’s technical confidence accumulates over time.

What matters here is not a dramatic wave of redundancies in the West. The mechanism is subtler. It’s about where future growth lands. It’s about the next thousands of roles - early career ladders, mid-career capability compounding, leadership pipelines - forming somewhere else.

That is a different kind of shift than we are used to discussing. It alters not just payrolls, but influence, learning, and where “the organisation” increasingly feels itself to be.

A familiar historical rhyme, with a different shape

If you grew up watching manufacturing migrate, the analogy is tempting. Factories moved; supply chains reorganised; politics followed, a decade late and badly phrased.

Knowledge work doesn’t migrate with the same visibility. There’s no factory gate to close, no town to photograph, no single date to point to. The language is smoother. The transition arrives as “global delivery”, “follow-the-sun”, “platform teams”, “shared services”. It can feel benign right up until the moment you notice the ladder has thinned.

And in the background, there is an unsettling political irony: manufacturing becomes a cultural battleground at the same time as high-value cognitive work becomes increasingly footloose. Nations talk; firms reorganise. These are different rhythms.

So why build huge offices in London?

Here’s the part that initially feels contradictory.

On one hand: enormous GCCs. On the other: huge commitments to prime office space in global cities. You might reasonably ask: if knowledge work can be distributed, why are organisations still writing very large cheques for very large buildings?

JP Morgan exemplifies this seeming paradox: building, via Brookfield, a 2 million square foot GCC in India (Asia’s largest) and a new 3 million square foot HQ in London.

I think the answer is that “office” is splitting into two distinct roles, and we have been slow to update the mental model.

Some work is increasingly treated as scalable production: build platforms, run systems, maintain models, improve workflows, keep the organisation operating. This can be concentrated where talent is deep, teams are stable, and execution can run at industrial scale. In a GCC.

Another kind of work is harder to industrialise: the work of commitment. The work of deciding. The work of arbitration when trade-offs are real, when risk is asymmetric, when reputation and legitimacy matter. Client relationships sit here. Regulatory accountability sits here. Leadership sits here. When something breaks, it’s not just the system that needs to recover; it’s trust.

London (and other top tier cities) remain valuable because they concentrate this second category. Not because everyone needs to be there every day to “do work” in the old sense.

AI changes what being together is for

AI makes this even more interesting.

Yes, AI enables asynchronous work. It lowers the cost of coordination across time zones and reduces the friction of documentation, handover, and context reconstruction.

But it also changes the bottleneck. When execution becomes cheaper, alignment becomes more expensive. When options multiply, judgement becomes scarcer. When systems become more capable, misalignment becomes more dangerous.

So the reason to be together shifts. It becomes less about sitting at a desk to complete tasks and more about calibrating shared understanding: framing problems, setting constraints, making trade-offs explicit, deciding what to delegate to machines, and agreeing what “good” looks like.

That is why I’ve long felt the office paradox: technology reduces the need to be in the office to execute work, yet increases the value of the office for the most human parts of work - co-creation, negotiation, trust-building, commitment.

Not five days a week. But regularly. Rhythmically. Intentionally.

A further twist: GCCs and AI are entangled

There is one more turn of the screw.

Many GCCs are, by design, places where work is standardised and systematised. That is what makes them scalable. It is also what makes them legible to automation. AI doesn’t just arrive as a tool used within a GCC; it arrives as a force that compresses parts of what the GCC was built to do.

This suggests a trajectory that’s less linear than the headlines imply: growth, then consolidation; expansion, then compression; large teams building systems, followed by smaller teams orchestrating them.

Which, again, has consequences for real estate. It changes not only where offices are needed, but what kind of offices make sense, and for how long.

Why this matters for commercial real estate

If you put these pieces together, it helps explain why the office market feels so difficult to read. We keep reaching for single-cause explanations - hybrid work, rates, supply, amenity - and they all matter. But underneath them is something deeper: organisations are learning how to scale capability without scaling domestic space in the way we once assumed.

That doesn’t mean “offices are over”. It means demand is becoming more selective and more functional. Some buildings and locations become more valuable because they support high-stakes human coordination. Others struggle because they were designed for a world where the office was primarily a container for execution.

That world is receding.

Where I’m going with this

This is the first note of 2026 because I suspect this is one of the most under-discussed structural shifts shaping work and cities right now.

In the next pieces, I want to do three things:

1. Look at GCCs as operating-model infrastructure, and what their scale tells us about where organisational intelligence is being built.

2. Explore the emerging split between execution and judgement, and what that implies for offices, portfolios, and city-centres.

3. Ask the deeper question beneath it all: participation. Who gets to be part of value creation as the machinery of cognition reorganises globally?

For now, one question to leave you with:

If the office is becoming less a place of work, and more a place where organisations make commitments - what should we stop building, and what should we build instead?

Part 3: Thoughts, Ideas, Actions for 2026… and Beyond.

Two weeks ago we looked at ’16 Emerging CRE Tech Trends’, and last week at ’10 Foundational Themes’. This week we’re going to look at ‘Personal and Organisational Transformation’, asking the harder question: what kind of professional, what kind of person, does this future require? The answer isn’t simply ‘more technical.’ It’s more human, more curious, more intentional, while simultaneously more integrated with machine capabilities than we’ve ever been.

As the gap widens between those who use AI and those who understand it, strategic fluency is non-negotiable. My next Generative AI for Real Estate People cohort begins in January - join us to move beyond the hype and start building a genuine competitive advantage. For details and to register visit antonyslumbers.com/course (or contact me if you’d like a tour).

Why this matters for real estate

Every shift described in this series of newsletters will reshape what our customers need from physical space. The AI-augmented workforce requires different offices; not just “smart buildings” but spaces designed for human-machine collaboration, for the deep work that AI can’t do, for the social connection that distributed teams crave when they do gather. Knowledge workers whose relationship with technology has fundamentally changed will make different choices about where to live and how they move through cities. The infrastructure demands of an AI-powered economy are already visible in data centre pipelines and energy constraints reshaping grid planning.

As CRE professionals, we don’t just use these technologies, we house the activities they enable. Our tenants, our buyers, our occupiers are all navigating the same transformation this series describes. Understanding these shifts isn’t optional; it’s core to anticipating demand. And anticipating demand is, ultimately, what this industry does.

That’s why a newsletter about CRE discusses cognitive pauses and ‘Renaissance Thinking’. Not because they’re nice to have, but because your customers are grappling with the same questions. The workplace strategist advising a corporate tenant needs to understand what “human+machine architectural shifts” mean for space planning. The residential developer needs to understand how AI-mediated work affects where people want to live. The investor needs to understand which cities will attract the curious, the adaptive, the cognitively sovereign. If you don’t understand these shifts as lived realities, not just abstract trends, you cannot serve your customers well.

PERSONAL TRANSFORMATION

The 10 Initial Steps to Become #FutureProof

These are the immediate, high-leverage actions an individual must take.

1. Develop AI Fluency (Not Just Literacy): Move beyond knowing what AI is to knowing how to use, critique, and apply Predictive, Generative, and Causal AI, focusing on immediate practice with frontier LLMs.

2. Reframe Your Mindset: Embrace AI as a ‘cyborg’, not a ‘centaur’. This means actively seeking workflows where human + AI achieves genuine synergy, outcomes neither could reach alone. But synergy requires you to bring something distinctive. Double down on developing judgement, critical thinking, empathy, nuanced decision-making, and emotional intelligence: the capabilities AI can simulate but not authentically provide. The cyborg model only works if the human component remains capable.

3. Become a Master of Prompt Engineering: Treat the ability to craft effective prompts that deliver precise, valuable, and creative outputs as a fundamental skill, using clarity, context, and constraints.

4. Understand Data and Its Value: Learn how to interpret, validate, and apply data in AI-powered decision systems, recognising that widespread data access means competitive advantage shifts to processing rather than owning data.

5. Adopt an Experimentation Mindset: Dedicate 5–10% of your working week to low-risk experimentation with new tools. “Low-risk” means: reversible, bounded in scope, learning-oriented rather than production-critical. Run a task through three different AI tools and compare outputs. Rebuild a workflow you know well using AI assistance and note where it helps and where it doesn’t. The goal isn’t immediate productivity, it’s building intuition for what these tools can and cannot do, so you can make better decisions when stakes are higher.

6. Prepare for New Business Models: The AI transition will reshape not just how work is done but what gets monetised. Hybrid and distributed working patterns are creating demand for flexible space models that barely existed five years ago. The explosion in compute requirements is driving unprecedented data centre development and straining energy infrastructure. For CRE professionals specifically: the buildings and places that prosper in the next decade may serve business models that don’t yet exist. Stay close to emerging use cases, not just established asset classes.

7. Think in Terms of ‘Space as a Service’: Be on top of the intersection of AI, automation, and physical infrastructure, aiming to provide spaces that enable every individual to be happy, healthy, and productive. This means moving from selling square feet/metres to selling outcomes: productivity, wellbeing, collaboration capacity. Having pioneered this term for many years, it is pleasing to see it now as ‘normal’ but AI will take it to another level: increasingly buildings will actively and passively collect data to optimise themselves and act as ‘Mavens’, ensuring that people who ‘should’ meet, actually do. I wrote about this at length here

8. Cultivate an Anti-Fragile Career: Design a career that thrives in volatility through adaptability, interdisciplinary knowledge, and AI augmentation, positioning yourself as an ‘AI-powered professional’.

9. Engage with the Societal Question: AI is a general-purpose technology, like electricity or the internet, with effects that extend far beyond any single application. The choices being made now about AI deployment, governance, and access will shape labour markets, urban form, and social cohesion for decades. This isn’t someone else’s problem. As professionals who shape physical environments, CRE practitioners sit closer to these consequences than most. Engage with the debates about AI ethics, transparency, and bias, not as abstract obligations, but as forces that will determine what kinds of places people want to live, work, and gather. The industry that houses human activity cannot be indifferent to how that activity is changing.

10. Build Your Network of Navigators: The transitions described in this series are too complex for any individual to track alone. Cultivate relationships with people in adjacent fields, technologists, urbanists, strategists, ethicists, who see different facets of the same transformation. The ‘Renaissance Thinkers’ who thrive won’t be isolated polymaths; they’ll be nodes in networks of diverse expertise. Share what you’re learning; learn from what others share.

Individual transformation is necessary but not sufficient. Organisations must also adapt their structures, processes, and advancement criteria to this new reality.

ORGANISATIONAL TRANSFORMATION

Organisational Architectures and Principles

Throughout this year, I’ve developed three distinct frameworks addressing different facets of AI adoption. They’re not a single system, each stands alone and serves different organisational needs. Think of them as lenses rather than steps: choose the one that addresses your most pressing challenge, or use all three for a comprehensive view.

Framework 1: Intentional Intelligence (Cognitive Defence)

For individuals asking: How do I stay cognitively sharp when AI makes shortcuts so easy?

This framework is deliberately different in tone. It addresses not what your organisation should do, but what you should protect. The risk of cognitive atrophy, what BetterUp Labs and the Stanford Social Media Lab described as “Workslop”, is real: the gradual erosion of capability that comes from offloading thinking to AI without intention. These five practices are maintenance routines for your organic intelligence. More on this here

1. Generative Primacy: Always attempt problems independently before consulting AI. This isn’t inefficiency, it’s exercise. The muscle you don’t use atrophies.

2. Strategic Friction: Deliberately re-introduce productive difficulty. Time-box AI access; schedule deep work without it. The goal isn’t to reject AI but to ensure you choose when to use it rather than defaulting to it.

3. Metacognitive Monitoring: Maintain conscious awareness of your own thinking process. Regularly ask: “What did I genuinely learn from this interaction? What would I have concluded without AI input?”

4. Contemplative Presence: Use micro-pauses - pre-prompt and post-response - to interrupt autopilot reactivity. This practice came from a Buddhist monk I shared a speaking platform with; it landed powerfully with an audience of workplace specialists. People are rightly worried about losing themselves to AI. A breath before prompting and after reading the response keeps you in the loop as a conscious agent, not a relay station.

5. Weekly Analog Practice: Commit to structured problem-solving sessions using only analog tools, pen and paper. Different modalities engage different cognitive capacities.

Framework 2: AI ROI Guiding Principles

For teams asking: How do we prove value and scale AI initiatives without losing control?

These four principles emerged from observing which AI implementations succeed and which become expensive disappointments.

1. Reimagine the Role, Not Just the Task: Redesign roles by focusing on uniquely human functions (creativity, relationships) while AI handles what it is good at. Task-level automation without role-level redesign creates fragmentation, not transformation.

2. Prove Value in Sprints, Then Scale with Confidence: Use rapid, evidence-based micro-sprints to test new workflows and measure concrete value before scaling. The graveyard of enterprise AI is full of projects that scaled before proving anything.

3. Empower the Person, Govern the Platform: Provide tools with autonomy but mandate that the human is always the expert-in-the-loop, accountable for the final output. Autonomy without accountability is chaos; accountability without autonomy is bureaucracy.

4. Capture & Compound the Learning: Build a living “Process & Prompt Library” to share successes and failures, creating a powerful learning flywheel. The organisation that learns fastest wins, but only if learning is captured and shared, not siloed in individual practice.

Framework 3: Human+Machine Architectural Shifts

For leaders asking: How do we redesign roles and progression when AI changes what ‘work’ means?

These three shifts describe how organisational architecture must evolve: not just processes, but career structures, knowledge systems, and advancement criteria.

1. From Execution to Judgement: Junior roles must shift from grunt work to supervised capability development. The “Resident Learner” model, where early-career professionals learn through AI-augmented work rather than despite it, replaces the apprenticeship of repetition with an apprenticeship of judgement.

2. From Tacit to Explicit: Senior expertise must be externalised into reusable frameworks. The ‘System Architect’ role emerges: experienced professionals whose job is to codify organisational knowledge into structures that AI can leverage and juniors can learn from. Expertise that remains tacit becomes a bottleneck; expertise that becomes explicit becomes a multiplier.

3. From Time-Based to Competency-Based Progression: Advancement driven by demonstrated capability, not tenure. When AI compresses the time required to develop certain skills, time-based progression becomes arbitrary. Define what competency looks like at each level; measure against that, not years served.

For more on this framework, see my detailed piece on Human+Machine Organisational Architecture

Conclusion

The next decade belongs to professionals who can operate at the intersection of human judgement and machine capability. The 3 newsletters in this series represent my attempt to map that intersection: the technologies arriving, the strategic shifts they imply, and the personal and organisational capabilities required to navigate them well.

But capability alone isn’t enough. We also need wisdom about where this is taking us, as individuals, as organisations, as cities. The AI transition isn’t just a professional challenge; it’s a human one.

For CRE specifically, the stakes are concrete. The spaces we develop, invest in, and manage will house whatever this transition becomes. We’ll see it in tenant requirements, in location decisions, in the infrastructure demands reshaping our cities. Understanding the transformation isn’t adjacent to our work - it is our work.

I hope this series helps you engage with both dimensions: the practical and the profound. The industry needs to think harder. These are my notes on what “thinking harder” might look like.

Thoughts, Ideas, Actions for 2026… and Beyond. Part 2.

Last week we looked at ’16 Emerging CRE Tech Trends’; This week we’re going to look at ’10 Foundational Themes’ - capturing the fundamental shifts required for the next decade, and defining the high-level competitive landscape.

1. The ‘Bicycle for the Mind’ Gets an Update

In 1981 Steve Jobs talked about how a computer was like a ‘Bicycle for the Mind’, a tool to amplify our mental capabilities through elegant digital engineering. The computer, like the bicycle, isn’t just a passive tool - it’s an efficiency multiplier that dramatically extends human potential.

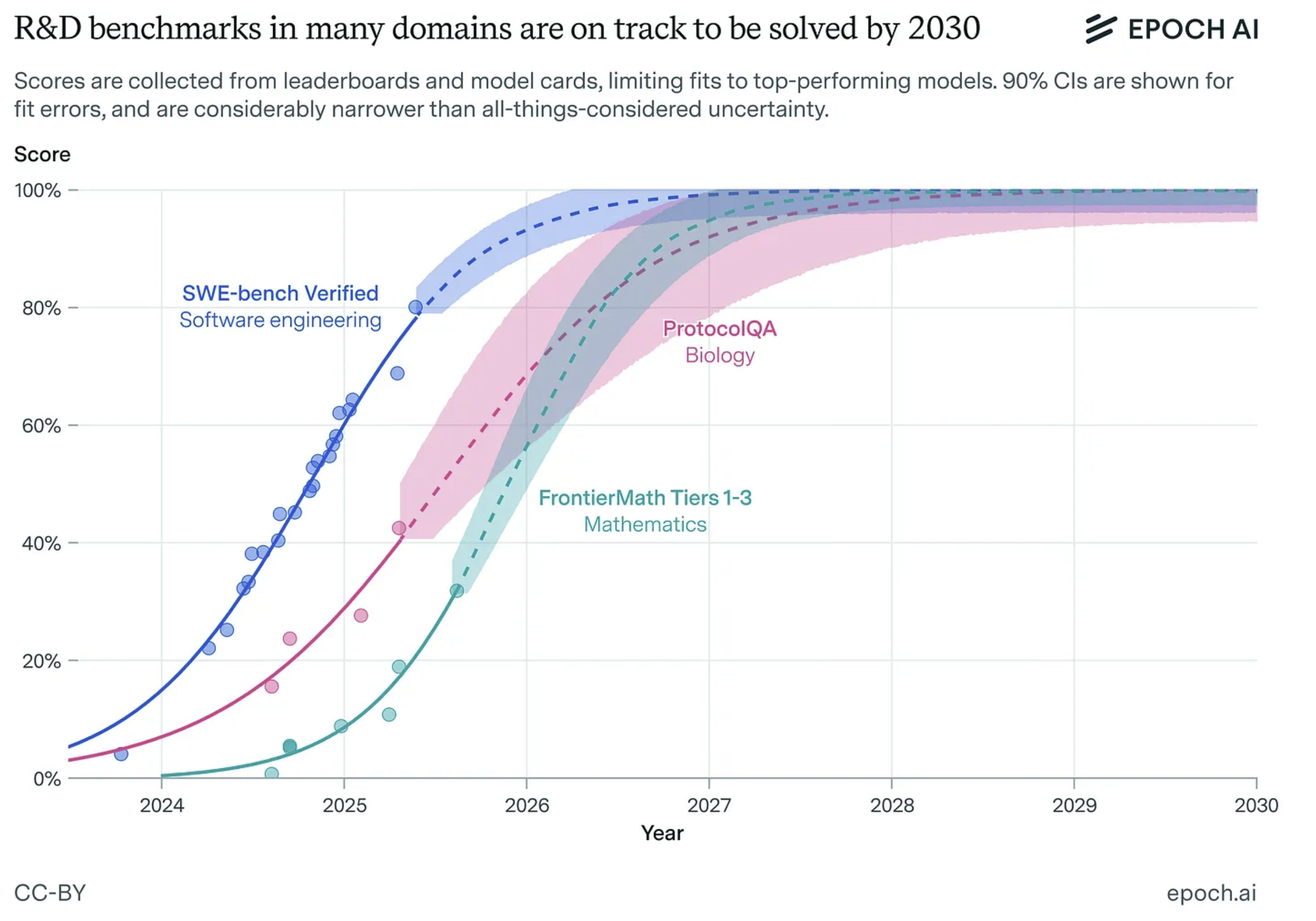

Bicycle though no longer feels adequate. In the last 8 years Nvidia’s GPUs (the chips that power most of ‘Planet AI’) have increased in power 1000X. According to the AI Research Company, Epoch AI, by 2030 we are likely to have 1000X the compute capacity that we have today. And R&D benchmarks in many domains are on track to be solved by 2030.

It needs to be foundational in your thinking that this scenario has a high probability of coming to pass, and therefore one must be anticipating what is likely to be possible, rather than over-indexing on current day capabilities. If one takes 9 months to develop a product/service it’s no using basing the specification on what can be done today.

What is arriving sooner than expected is the ‘LLMs as the kernel of a new operating system’ idea put forward by famed AI Research Andrej Karpathy in 2023. This is the concept that instead of needing to program a computer, increasingly one will be able to use natural language to simply ask for what we want. An LLM will be able to interpret this and pull in the necessary specialist tools as required. ‘The hottest new programming language is English’, as he says.

This is going to leave us less as individual cyclists and more as orchestrators of armies of ‘e- bikes’, which we don’t need to pedal, just steer.

Unbundling & Rebundling

There is no question that there are going to be winners and losers in an AI mediated world. Where you end up is largely going to be a function of how well you understand the way AI is going to unbundle and rebundle almost all knowledge work.

Currently each of us has a job, a role. This typically involves a series of goals that we have to achieve in order to fulfil our responsibilities. In turn each of these goals consist of a series of tasks we need to perform, or execute, to fulfil each goal. In effect, this is what every job description is specifying.

As technology develops it can perform ‘some’ of our Tasks. But Goals and Roles are still overseen by Humans.

Over time technology will enable a series of Tasks, that make up specific Goals, to be performed entirely by an ‘AI Agent’. These will be discreet mini applications that are tasked with performing X, and provided with the necessary capabilities to do so.

This means that some tasks will remain as a collection of tasks performed in part by humans, and in part by technology, whereas other goals will be possible to achieve solely through the application of technology. That goal can then be removed from the ‘job description’ and handled separately.

What might also occur is that multiple goals can be fulfilled by pulling from a repository of ‘AI Agents’ that can be combined in ways that enable them to have utility across multiple domains. Maybe with 30 ‘AI Agents’ we can deal with 50, or 100 goals.

Think of it like Lego; with the same pieces we can combine them in different ways and create a multitude of different things.

And this ‘unbundling & rebundling’ process is guaranteed. Either wilfully, or by having it imposed on us by changing circumstances.

The process is also how we will be able to fully leverage AI. One cannot simply bolt on AI to existing processes and expect transformational outcomes. Many are doing this, but already we have plenty of research showing it does not work.

We don’t need to add cream on the top of our cake - we need to bake a new one!Fast, Agile, Ultra-Productive Superteams

We are seeing the emergence of small, highly skilled teams leveraging AI augmentation to achieve exceptional productivity, challenging the size and speed of traditional large firms. Whilst the meme about ‘Single Person Unicorns’ is probably over-egging it we are already seeing various software companies, such as Midjourney, Cursor, Lovable, with dozens of employees by hundreds of millions in ARR.

Software is of course perfect for leveraging AI, more so than other industries, but there is enough evidence of quite dramatic bumps in productivity at the team level, to take this seriously.

At a corporate level achieving high productivity gains is harder and slower, due to the usual ‘Normal Technology’ …frictions: slow organisational and institutional change, the need to redesign workflows and incentives, regulatory and safety constraints, and the simple fact that deep adoption demands far more than merely making powerful tools available.

But for startups, or scale-ups, these don’t apply, and the ability of new companies to outperform incumbents is dramatically increased by AI.

Over the next two years I envisage many incumbents suddenly coming up against these new entities… and losing out.

Here’s a possible CRE example:

The “Capital Sniper” Team (Investment & Acquisitions)

The Old Way: A Head of Acquisitions manages an army of Junior Analysts. They manually read IMs, input data into Excel, and take 2 weeks to screen a deal.

The Superteam (2-3 People): One Senior Deal Maker + One Data Architect + A fleet of AI Agents.

The Workflow: AI Agents ingest every listing instantly, extracting data and running it against the firm’s investment thesis.

The Advantage: They don’t look for deals; the deals are surfaced automatically. They underwrite 500 deals a week, not 5.

Expect a few ‘Code Reds’ to be issued.Removing Friction and Enabling Discovery

Jeff Bezos said in 2021 that he thinks less about what’s going to change and more about “What’s not going to change in the next 10 years?”—because you can build a business strategy around things that are stable in time.

In commercial real estate, I’d posit that “Removing Friction and Enabling Discovery” will be forever constant. Our customers want to do what they need to do painlessly, and based on the best possible information.

But to understand why this matters now, we need to recognise a deeper shift: real estate has moved from being a Bond to being a Business.

The 25-year lease with upwards-only rent reviews is largely dead. The “lock up and leave” operating model is over. Our customers are now our users, not just our investors - and for investors to achieve the returns they want, we must put user interests first. The smart money has recognised this as opportunity, not threat: today, you can differentiate yourself like never before.

Friction has been endemic to our industry. Jargon-filled leases. Inflexible terms. Manual processes for payments, access, and visitor management. Opaque pricing. Poorly designed spaces that don’t support actual work.

Meanwhile, “enabling discovery” means making it easy for people to find what they need: seamless access to information, personalised experiences, data-driven insights, and spaces designed for serendipitous connection.

Technology, especially AI, is the key. But the level of service now required cannot be delivered economically through humans alone. Automating the “human touch” authentically, rather than robotically, is becoming a superpower for real estate operators.

The industry is at a liminal point. Removing friction and enabling discovery are the foundations upon which the winners will build.

Redefining ‘what is the best affordable option?’

In business, the quality of service we receive is directly tied to what we can afford - and the same applies to the quality we provide. Every service operates within defined price points: pay more, get more. For decades, this has created a clear divide between those who can afford premium offerings and those limited to more basic options.

Generative AI is going to upend this apple cart. It is going to redefine what is meant by ‘affordable’. In terms of the services you receive, or the services you supply. In short, it is going to massively redefine ‘the best affordable option’.

Many services that were previously ‘White Glove’ - only available to the richest and most prestigious companies - are going to be commoditised and made available to all. When financial models take 2 hours not 2 weeks to develop, when research takes 1 hour instead of 1 month, and when software apps are deliverable in 6 days instead of 6 months, the economics and dynamics of markets totally change.

This could mean services are no longer profitable to deliver, if kept as ‘White Glove’ ones, but if repositioned to be sold to a much larger market that did not exist at the old price points, the game changes entirely.

At the core, AI is going to be, in many cases, ‘the best affordable option’.

Outcomes as a Service (OaaS)

The limitations of the pure SaaS model are becoming apparent. While SaaS democratised access to powerful software, it left the burden of achieving results squarely on the client. Companies purchased subscriptions, but the responsibility for implementation, adoption, and tangible improvement remained with them.

AI changes the equation. Software alone is not enough - the operational landscape now requires software, plus data wrangling, AI implementation, analysis, and definable outcomes. Most buyers don’t want to orchestrate all of this; they just want X to perform according to A, B, and C.

Consider the difference between subscribing to an energy management platform and partnering with a provider who guarantees a specific percentage reduction in energy consumption, with fees tied to achieving that target. That’s OaaS: selling outcomes, not access.

In CRE, this might mean committing to specific tenant satisfaction scores, delivering guaranteed sustainability metrics, or ensuring space utilisation hits agreed benchmarks - with payment contingent on results.

This shift will force transformation on the supply side. PropTech companies will need new roles, such as ”Outcome Managers,” “Value Engineers”, and new pricing models: performance-based fees, risk-sharing agreements, value-based pricing tied to realised benefits.

Who’s positioned to win? Existing PropTech players have the technology but must build service capabilities. Specialised startups can focus on niche outcomes. And the large CRE services firms, JLL, CBRE, Cushman & Wakefield, have the client relationships and industry knowledge, but face the classic Innovator’s Dilemma: can they cannibalise existing revenue streams fast enough?

Increasingly, selling outcomes, not software, will be the norm.

#HumanIsTheNewLuxury

This has been my theme of the year. As the world gets ever more AI-mediated, it will actually be human skills that command premium value.

We humans tire of technology remarkably quickly. We strive to acquire the next big thing, are in thrall to it briefly, then become bored. It wasn’t long ago that maintaining a phone signal in a car was hit and miss; now we rage when 4K streaming drops at 80 mph. As Shania Twain put it: “Okay, so you’re a rocket scientist / That don’t impress me much.”

Technology will move into the background, powering much of what happens around us, but given no more thought than a light switch. What we’ll pay for is what sits on top: experiences that delight, connections that feel authentic, craftsmanship that carries the mark of human hands.

In a world of mechanical perfection, we will actively seek out imperfection. The imperfect will be unique; the perfect, a commodity. Think vinyl versus CD - the CD is technically superior, but vinyl speaks to your soul.

For real estate, this points in specific directions: high-touch concierge services where AI provides the insight but humans deliver the experience; curated spaces that reflect human judgment, not algorithmic optimisation; community-centric developments that foster genuine connection; relationship-based transactions for deals that matter.

To be clear, being a great human with great human skills won’t be enough. Each of us will need to be AI Fluent, orchestrating technology while creating and curating the intensely human experiences that constitute “work.” This is not a call for Luddism; it’s a demand for the kind of skill that makes everything look effortless.

The challenge will be making this the norm, not just a luxury.

Evolving Real Estate: Form, Purpose, Location

“We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.”

If we want to benefit from the themes discussed here, we need the right real estate. Churchill was explaining how our internal environment shapes us: form, purpose, and location matter. Real estate is an input to whatever output is created within it.

Technology now enables us to do “Everything Everywhere All at Once.” RTO mandates fail because they fight against the tide of technology. The world of everyone in the office, five days a week, is fundamentally a pre-internet construct - it’s just become clearer as capabilities have developed.

So what matters when pervasive AI means “the machines” are doing much of our work? I’d argue for six pillars of human-centric real estate:

- Health & Wellbeing: Environmental quality - lighting, acoustics, temperature, air quality - directly affects cognitive function. Get this right and you enable people to perform at their best.

- Ergonomics & Comfort: Physical quality designed for actual use, by actual users.

- Technology Integration: Seamless, friction-free - not ten minutes getting the AV to work before every meeting.

- Community & Connectivity: Over the next decade, this becomes THE purpose of commercial real estate. Everything else gets offloaded to machines. Why else would we commute except to do what we cannot do elsewhere?

- Flexibility & Adaptability: Sam Altman has a sign above his desk: “No one knows what happens next.” If he doesn’t know, nobody does. Billions of square feet have already outlived their product/market fit. We must create spaces people can reconfigure.

- Sustainability: Non-negotiable and foundational.

But form is only part of the story. Purpose is shifting: we don’t NEED an office to work, or a shop to shop - we have to be made to WANT them. And location is morphing: Central Business Districts are becoming Central Social Districts.

Beyond individual buildings, four broader shifts are coming:

- Decentralised hubs: The biggest agglomeration of talent is now on the internet. Distributed working is the future; real estate must supply to this demand.

- Micro-locations: Hyper-local, mixed-use developments with deep understanding of customer wants and needs.

- Transportation-responsive design: Autonomous vehicles are here - “just not evenly distributed.” When we don’t need parking, what happens to all that space?

- Fluid space allocation: A curb as delivery zone in the morning, rideshare pickup in the afternoon, restaurant seating in the evening. 24 hours in a day - use them.

- Whoever truly understands the drivers of successful spaces and places will make fortunes. And vice versa.

#SpaceasaService loves Generative AI

This grew out of a feeling that the same characteristics that make a company embrace #SpaceasaService are the ones that make them active adopters of Generative AI. Both are fundamentally creative movements, looking to enable humans and machines to work together to produce things neither could achieve alone.

And as it happens, a new study (’Employee Centricity in an AI World’) by BCG and Columbia University confirms this:

“Employee-centric organisations are 7X more likely to be AI mature compared to orgs who are beginning/emerging in employee centricity.“

And: “The same capabilities needed for successful flexible (hybrid) work arrangements—transparent communication, focusing on outcomes over activities, cross-functional coordination—are also crucial for effective AI transformation.“

The implication for real estate strategy is significant. We’re likely heading toward a market that looks like this:

- Top 15-20%: Large multinationals with in-house scale to create exceptional workplaces in exceptional buildings.

- Next 40-45%: #SpaceasaService - either through high-quality flex operators or by having operators run their buildings for them. CBRE’s acquisition of Industrious suggests this is now a core strategic bet.

- The remainder: Shrinks, goes fully distributed, or disappears. There is no future for low-to-medium quality commodity office space.

If 30-40% of existing office stock is already obsolete or heading there fast, the question becomes: which side of this divide are you positioning for?

As I’ve been saying all year—mindset matters.

We Need a Bigger Pie

You’ve heard the saying: “AI won’t take your job - someone using AI will take your job.” This is dangerously misleading. It implies 1:1 displacement - your job goes to another person who’s better with tools. This ignores the maths of leverage.

AI doesn’t just make workers better; it makes them exponentially faster. If one asset manager equipped with AI agents can perform the underwriting, market analysis, and reporting work of five junior analysts, the remaining four jobs aren’t “taken by someone using AI.” They simply evaporate.

The fundamental flaw focuses on the survivor and ignores the displaced.

In a stagnant macroeconomic environment, efficiency gains result in headcount reduction, not output expansion. The absolute certainty is this: AI means we will need fewer people to achieve our current level of output.

Which means we need a bigger pie.

But how? Not through efficiency alone - that just concentrates gains among fewer people. We need genuine expansion: new industries, new markets, new categories of value.

AI is already unlocking markets that were previously inaccessible. Language translation enables global reach; analytics reveal untapped customer segments; personalised services that once required armies of staff become viable at scale. Barriers to entrepreneurship are falling - smaller players can now compete with established enterprises through AI-powered automation.

And we need to rethink value itself. In an AI-augmented economy, intangible assets, data, knowledge, creativity, curation, take on heightened significance. Companies must move beyond efficiency gains and reimagine what constitutes value when intelligence is increasingly commoditised.

Without intentional effort, AI risks concentrating wealth among a small subset of individuals and companies. The bigger pie only matters if more people get a slice.

Surveys show that employees in the West are anxious about AI while the C-suite remains optimistic. There is a major disconnect, because employees understand the incentives. For a certain type of management, AI is a zero-sum efficiency tool. It takes a different mindset to see it as a growth catalyst.

So what’s required?

- Businesses must embrace AI for expansion, not just cost-cutting.

- Policymakers must create frameworks that encourage responsible innovation and workforce transition.

- Individuals must invest in skills that complement AI, creativity, judgment, relationship-building, and assess whether their organisation sees AI as growth engine or headcount reducer.

The next decade will determine whether AI-driven prosperity is broadly shared or narrowly concentrated. That’s a choice, not an inevitability.

Conclusion

These ten themes are not predictions to debate but a roadmap to a destination that’s largely certain. The precise route will vary, by sector, by firm, by individual circumstance, but the direction of travel is clear. AI will unbundle and rebundle knowledge work. Small teams will outcompete slow incumbents. Human skills will command premium value precisely because everything else becomes commoditised. Real estate will either serve human needs brilliantly or become obsolete.

The framework is deliberately flexible. You don’t need to act on all ten themes simultaneously. But you do need to understand how they interconnect, because they will shape the competitive landscape whether you engage with them or not.

What makes this moment different from previous technology transitions is the speed and the scope. We’re not adapting to one new tool; we’re adapting to a new substrate for all knowledge work. That’s daunting. But it’s also genuinely exciting. The organisations and individuals who approach this with curiosity rather than fear, who see growth rather than just efficiency, who invest in human capability alongside technological capability - they will thrive.

Work could be, in almost every way, better and more fulfilling in an AI-fluent world. We remain the apex species. These are super-tools, and it is for us to use them in ways that are positive and life-enhancing.

The destination is a bigger pie, more human-centric spaces, and work that plays to our distinctly human strengths. The road there is ours to choose.